Author

Akira Noda - VoicePing Inc.

TL;DR

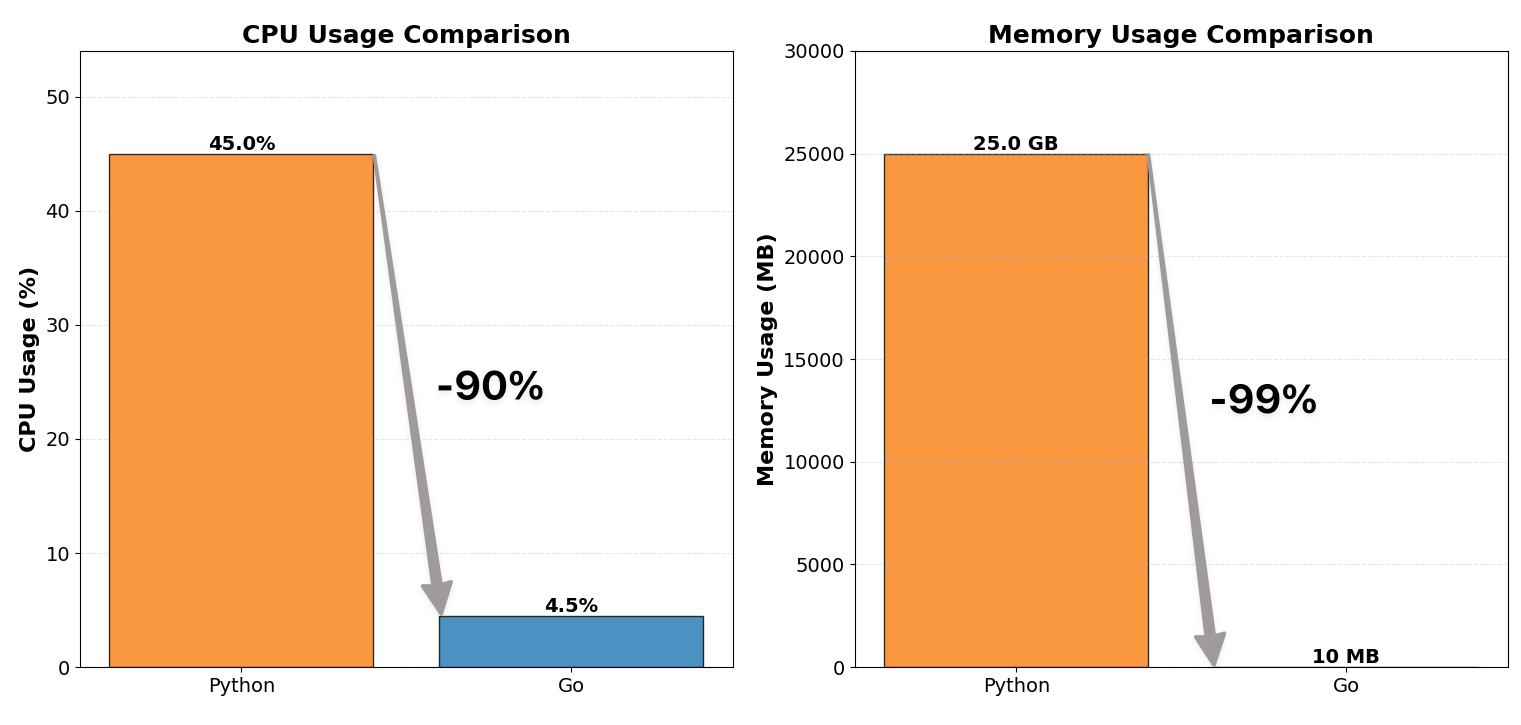

We rewrote our WebSocket proxy server from Python to Go and reduced CPU usage to 1/10 and memory consumption to 1/100.

The project not only improved resource efficiency but also taught us a crucial concurrency lesson:

Keep locks as small and as few as possible.

Context

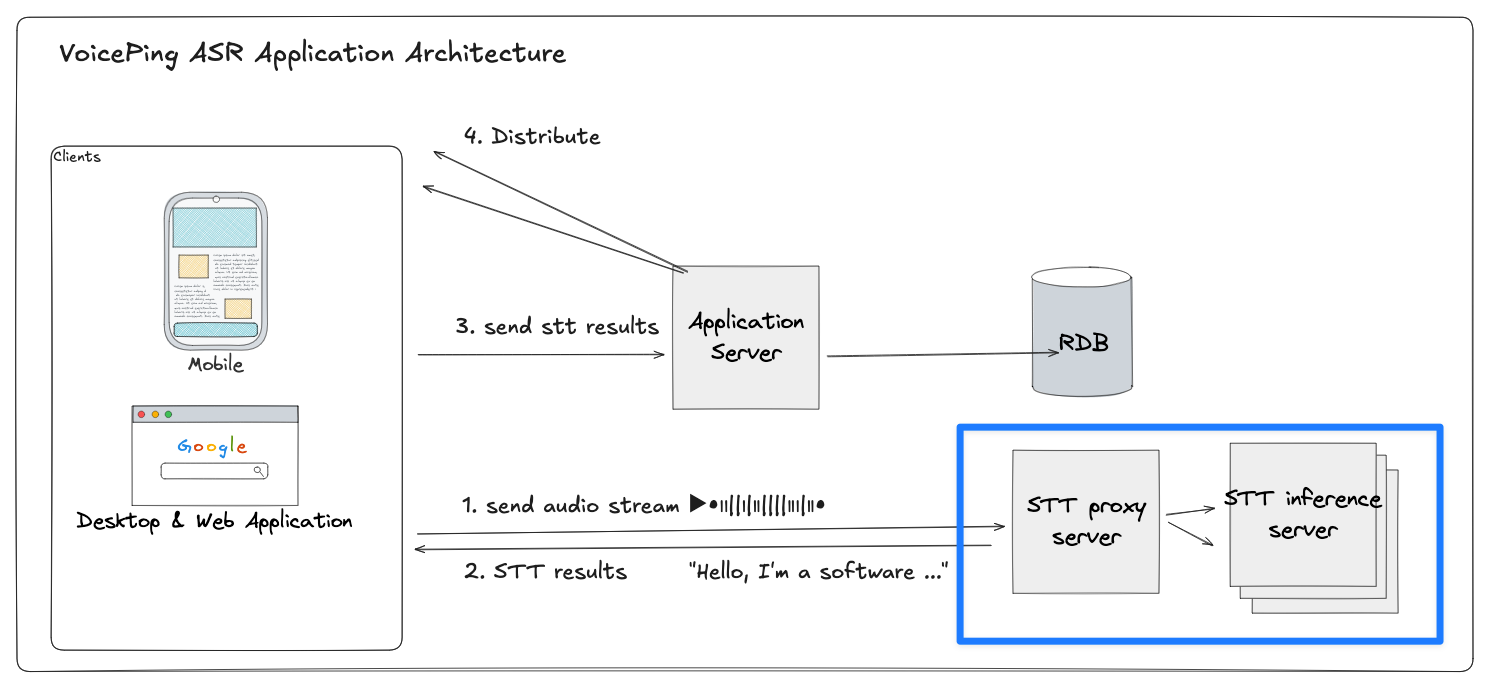

Our system is a real-time STT (speech-to-text) and translation pipeline used in VoicePing, where each client device streams audio to our backend for speech-to-text and translation in multiple languages.

The WebSocket proxy server sits in the middle of this pipeline:

System architecture overview

- Each client maintains a persistent WebSocket session with the STT proxy

- The proxy relays audio packets to one of several GPU-based inference servers

- Waits for transcribed text and streams back partial transcripts and translations

This architecture must handle thousands of concurrent real-time audio sessions — with sub-second latency.

However, our previous Python-based proxy became the bottleneck.

Before: Python Proxy (Inefficient)

Our first proxy server was implemented in Python (FastAPI + asyncio + websockets) and deployed using Gunicorn with multiple worker processes.

It worked fine at small scale but quickly hit resource limits under production traffic:

| Metric | Before (Python) | After (Go) |

|---|

| CPU usage | ~12 cores, 40–50% | ~12 cores, 4–5% |

| Memory usage | ~25 GB | ~10 MB |

Why Python Struggled

Despite being asynchronous, Python’s architecture imposed several systemic bottlenecks:

Single-Threaded Event Loop:

The asyncio model multiplexes thousands of coroutines on a single thread. This means only one coroutine runs at a time — others wait until the loop yields control. Under heavy I/O, this single loop becomes a central choke point, especially for WebSocket workloads with constant read/write events.

Gunicorn Multiprocessing:

To use all CPU cores, we spawned multiple worker processes. Each process loaded a full Python runtime and app state — multiplying memory usage linearly.

Heavy Task Contexts:

Each WebSocket connection keeps its own stack frames, futures, and callbacks — consuming large memory per connection.

Interpreter Overhead:

Every coroutine runs inside the CPython interpreter, adding dynamic type checks and bytecode dispatch overhead.

As a result, even though the system appeared concurrent, it was sequential at its core — every coroutine waited on the same event loop, amplifying latency and CPU load as connection counts rose.

It was inevitable — Python’s model simply wasn’t suited for long-lived, high-throughput, low-latency WebSocket multiplexing at this scale.

So we rewrote it in Go.

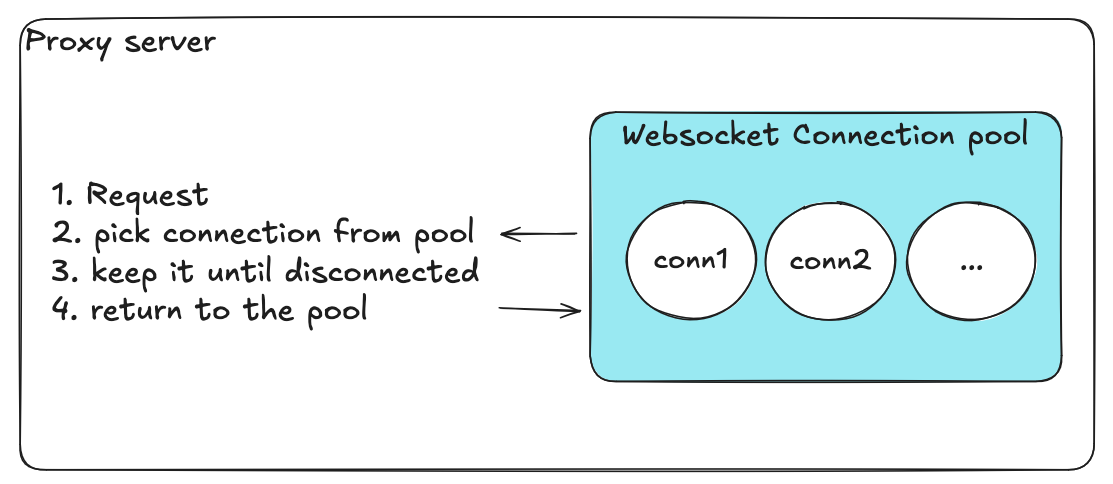

Birds-eye View of the Proxy Server

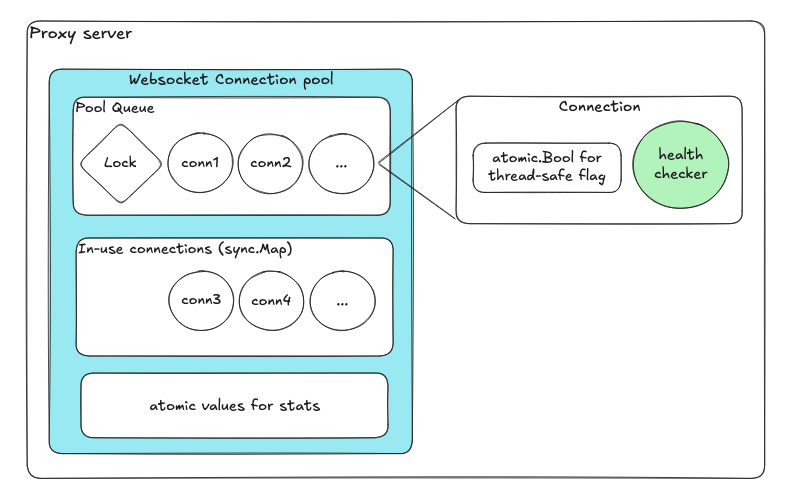

Proxy server architecture with connection pools

- Connection manager: handles routing and lifecycle of client connections

- WebSocket connection pools: manage reusable backend connections for each inference server

Each pool corresponds to one inference target (e.g., A or B), and holds a limited number of pre-established WebSocket connections.

This architecture allows the proxy to:

- Balance load efficiently across inference servers

- Avoid frequent connection establishment overhead

Functional Requirements for Connection Pool Management

Connection pool functional requirements

| Requirement | Purpose |

|---|

| Pick an available connection | Each incoming request must quickly obtain a ready-to-use backend connection without blocking other clients. Ensures low latency and smooth load balancing. |

| Return connection to pool | Once a client session ends, the connection should be released and made available for reuse. Minimizes overhead of repeatedly opening/closing connections. |

| Keep only healthy connections | Periodic health checks remove or recreate failed connections. Prevents unhealthy connections from accumulating and causing silent failures. |

| Sync database config | Periodically synchronizes backend connection configuration from a central database, allowing dynamic scaling without restarts. |

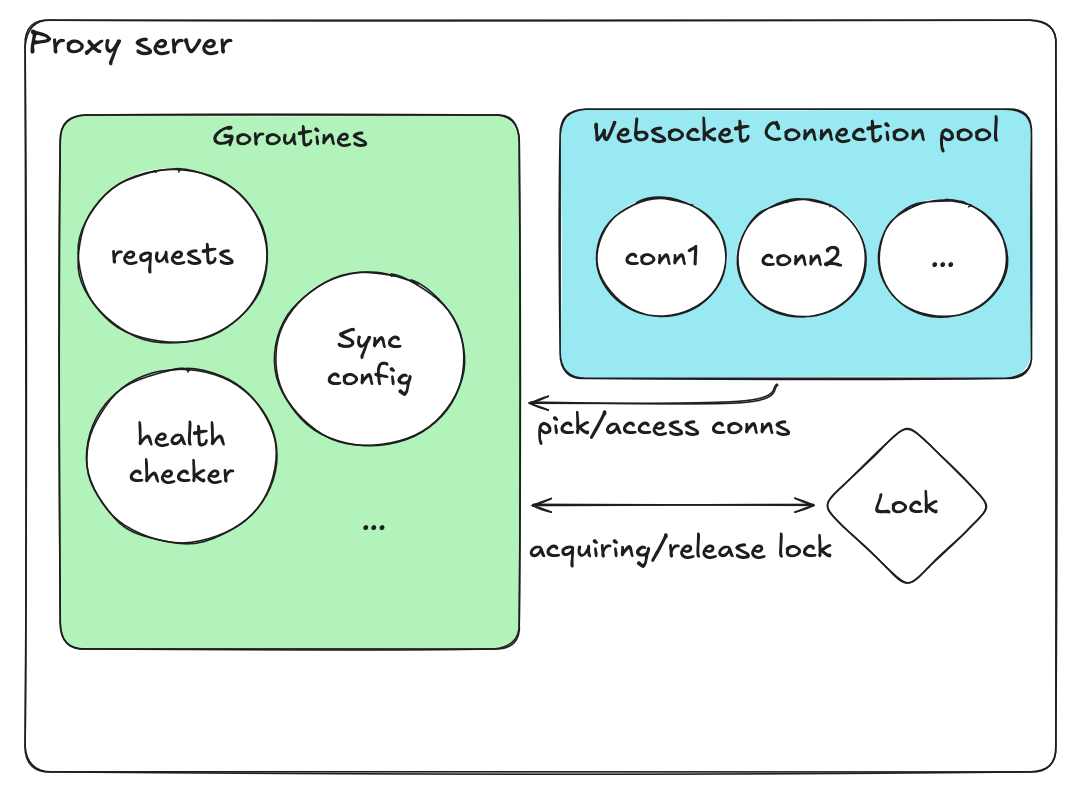

First Design (Naive)

Initial design with global mutex

- A single array holding all connections

- Boolean flags for “in-use” / “available” states

- One global lock for all operations

Picking a connection involved:

- Acquiring the lock

- Scanning the array to find an available connection

- Marking it as “in use”

- Releasing the lock

Returning a connection worked similarly — acquire the lock, flip the flag, release the lock.

We also had a separate goroutine to check database configuration periodically. This goroutine refreshed backend settings such as server lists or pool sizes from the database, ensuring the proxy always had the latest configuration without requiring a restart.

A separate health-check goroutine periodically scanned all connections, removed unhealthy ones, and added new ones when needed.

// ────────────────────────────

// FIRST DESIGN (naive, global mutex)

// Single slice + flags, one coarse-grained mutex.

// ────────────────────────────

type Conn struct {

id string

ws *websocket.Conn

inUse bool

healthy bool

}

type Pool struct {

mu sync.Mutex

conns []*Conn

maxSize int

dialURL string

}

// newConn dials a backend and returns a connected *Conn.

// NOTE: In this first design we (incorrectly) call this under the global lock.

func (p *Pool) newConn(ctx context.Context) (*Conn, error) {

d := websocket.Dialer{}

c, _, err := d.DialContext(ctx, p.dialURL, nil)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

return &Conn{

id: uuid.NewString(),

ws: c,

inUse: false,

healthy: true,

}, nil

}

// ────────────────────────────

// AdjustPool

// Check capacity vs current size; if not full, fill it.

// BAD PATTERN: holds the global mutex across slow I/O (dial).

// ────────────────────────────

func (p *Pool) AdjustPool(ctx context.Context) error {

p.mu.Lock()

defer p.mu.Unlock()

cur := len(p.conns)

if cur >= p.maxSize {

return nil

}

needed := p.maxSize - cur

for i := 0; i < needed; i++ {

conn, err := p.newConn(ctx)

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("adjust: dial failed: %w", err)

}

p.conns = append(p.conns, conn)

}

return nil

}

// ────────────────────────────

// GetPoolStats

// Return total / in-use / available counts.

// BAD PATTERN: O(n) scan under global lock every call.

// ────────────────────────────

type PoolStats struct {

Total int

InUse int

Available int

Healthy int

Unhealthy int

}

func (p *Pool) GetPoolStats() PoolStats {

p.mu.Lock()

defer p.mu.Unlock()

var inUse, healthy int

for _, c := range p.conns {

if c.inUse {

inUse++

}

if c.healthy {

healthy++

}

}

total := len(p.conns)

return PoolStats{

Total: total,

InUse: inUse,

Available: total - inUse,

Healthy: healthy,

Unhealthy: total - healthy,

}

}

// ────────────────────────────

// HealthCheck

// Ping all connections and mark healthy=false on failures.

// BAD PATTERN: holds global lock during network I/O & mutates in place.

// ────────────────────────────

func (p *Pool) HealthCheck(ctx context.Context, timeout time.Duration) {

p.mu.Lock()

defer p.mu.Unlock()

deadline := time.Now().Add(timeout)

for _, c := range p.conns {

if c.ws == nil {

c.healthy = false

continue

}

if err := c.ws.WriteControl(websocket.PingMessage, []byte("ping"), deadline); err != nil {

c.healthy = false

_ = c.ws.Close()

c.ws = nil

continue

}

c.healthy = true

}

}

Issues in the First Design

Despite working in small tests, the initial pooling model broke down under load. We observed:

Incorrect total count (overshoot/undershoot):

Concurrent pick/return operations mutated the same slice + flags under one coarse lock, so retries and timeouts occasionally double-returned or lost a connection, drifting past the max or starving the pool.

Racey concurrent access → crashes & corrupt state:

Health-check and metrics goroutines contended with request handlers; long health checks held the global lock, while readers sometimes observed half-updated flags, triggering panics or “no available connection” errors despite capacity.

Goroutine leaks:

Failed dials and timed-out health checks weren’t always canceled or reaped; retries spawned new goroutines while references to old ones lingered.

Fragile observability:

Counters derived from the slice + flags frequently disagreed with reality, making alerts noisy and masking real incidents.

Lock contention & latency spikes:

O(n) scans for an available slot under a single lock amplified tail latency as concurrency increased.

Root cause in one line: too much shared state guarded by one wide, long-held lock, plus operations (health/metrics) that should have been independent competing for that same lock.

Revised Design

Lock-free design with atomics and channels

| Component | Purpose |

|---|

| Queue for available connections | Enqueue/dequeue handles internal locks automatically |

| sync.Map for in-use connections | Lock-free concurrent map |

| Atomic variables | Health flags and counters |

| Dedicated goroutine per connection | Independent health checks |

package pool

import (

"context"

"errors"

"net/http"

"sync"

"sync/atomic"

"time"

"github.com/google/uuid"

"github.com/gorilla/websocket"

)

// ────────────────────────────

// Conn (a single reusable backend WebSocket connection)

// ────────────────────────────

//

// ✅ GOOD PATTERN:

// - Keep each connection self-contained and concurrent-safe using atomics.

// - Encapsulate health logic inside the Conn itself (no shared state mutation).

// - Avoid external locks and let each conn manage its own goroutine lifecycle.

type Conn struct {

id string

ws *websocket.Conn

healthy atomic.Bool // ✅ lock-free health status flag

lastPing atomic.Int64 // ✅ atomic timestamp for last heartbeat

}

// ✅ GOOD PATTERN: Explicit small helper methods (no external mutation)

func (c *Conn) ID() string { return c.id }

func (c *Conn) IsAlive() bool {

return c.healthy.Load()

}

// ✅ GOOD PATTERN: Safe close, idempotent and isolated

func (c *Conn) Close() error {

if c.ws != nil {

return c.ws.Close()

}

return nil

}

// ✅ GOOD PATTERN: Health loop runs independently per connection

// - No shared/global lock.

// - Non-blocking heartbeat.

// - Fails fast and marks itself dead without blocking pool operations.

func (c *Conn) StartHealthLoop(ctx context.Context, interval time.Duration) {

t := time.NewTicker(interval)

defer t.Stop()

for {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

return

case <-t.C:

deadline := time.Now().Add(interval / 2)

if err := c.ws.WriteControl(websocket.PingMessage, []byte("ping"), deadline); err != nil {

c.healthy.Store(false)

_ = c.Close()

return

}

c.lastPing.Store(time.Now().UnixNano())

c.healthy.Store(true)

}

}

}

// ────────────────────────────

// ConnPool (fast path only — no dialing, no blocking I/O)

// ────────────────────────────

//

// ✅ GOOD PATTERN:

// - Separate responsibilities: pool only manages available connections.

// - No dialing / blocking I/O under locks.

// - Use channel buffering and atomic counters for concurrency safety.

// - Eliminates coarse-grained global mutex.

type ConnPool struct {

available chan *Conn // ✅ buffered channel for ready conns (lock-free)

inUse sync.Map // ✅ concurrent map for tracking active conns

statsIn atomic.Int64 // ✅ atomic counters (no need for locks)

statsOut atomic.Int64

}

// ✅ GOOD PATTERN: Explicit, fixed-capacity pool construction

func NewConnPool(capacity int) *ConnPool {

return &ConnPool{

available: make(chan *Conn, capacity),

}

}

func (p *ConnPool) Capacity() int { return cap(p.available) }

// ✅ GOOD PATTERN: Non-blocking Acquire

// - Never holds locks while waiting for I/O.

// - Returns instantly if no conn available.

func (p *ConnPool) Acquire(ctx context.Context) (*Conn, error) {

select {

case c := <-p.available:

p.inUse.Store(c.id, c)

p.statsIn.Add(1)

return c, nil

case <-ctx.Done():

return nil, ctx.Err()

default:

return nil, errors.New("no connection available")

}

}

// ✅ GOOD PATTERN: Non-blocking Release

// - Never waits for space in the channel.

// - Drops unhealthy or excess conns immediately.

// - No global mutex.

func (p *ConnPool) Release(c *Conn) {

p.inUse.Delete(c.id)

p.statsOut.Add(1)

if c.IsAlive() {

select {

case p.available <- c:

// ✅ returned to pool safely

default:

// ✅ pool full → discard stale conn safely

_ = c.Close()

}

} else {

// ✅ unhealthy → close immediately

_ = c.Close()

}

}

// ✅ GOOD PATTERN: Offer is used by reconciler (external goroutine)

// - Keeps dialing/repair logic out of hot path.

// - Backpressure-safe with non-blocking insert.

func (p *ConnPool) Offer(c *Conn) bool {

select {

case p.available <- c:

return true

default:

return false

}

}

// ────────────────────────────

// Stats and Metrics

// ────────────────────────────

//

// ✅ GOOD PATTERN:

// - Lock-free snapshot using atomics.

// - Avoids holding locks during metrics collection.

type PoolStats struct {

Capacity int

Available int

InUse int

Acquired int64

Released int64

}

// ✅ GOOD PATTERN: Snapshot safely aggregates pool state without blocking

func (p *ConnPool) Snapshot() PoolStats {

inUseCount := 0

p.inUse.Range(func(_, _ any) bool {

inUseCount++

return true

})

return PoolStats{

Capacity: cap(p.available),

Available: len(p.available),

InUse: inUseCount,

Acquired: p.statsIn.Load(),

Released: p.statsOut.Load(),

}

}

Each component operates independently with no pool-wide locks. The number and scope of locks dropped dramatically.

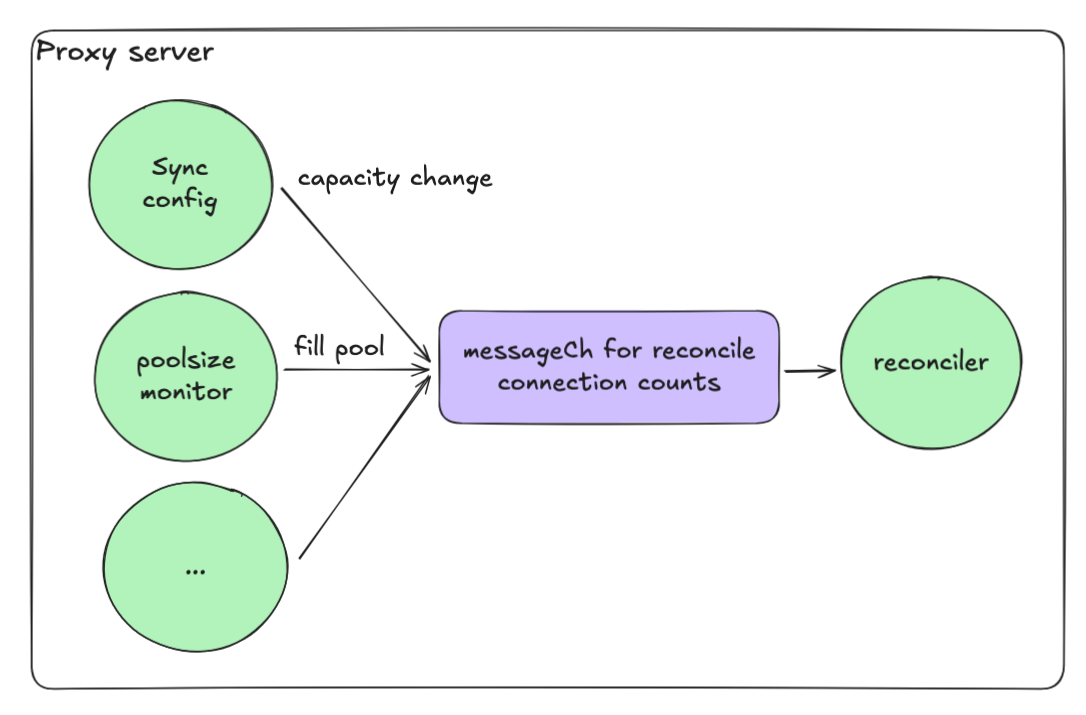

Event-Driven Reconciliation

Reconciliation worker pattern

- Each operation sends a message into a channel (messageCh)

- The reconciliation goroutine processes these messages sequentially

- This ensures no race conditions

This model allowed us to handle high concurrency while keeping the system deterministic and safe.

type ServerConnectionPool struct {

ctx context.Context

cancel context.CancelFunc

reconcileCh chan struct{}

logger *zap.Logger

// ... other fields ...

}

// ✅ GOOD PATTERN: Constructor wires a buffered (size=1) signal channel to enable coalescing.

func NewServerConnectionPool(logger *zap.Logger /* ... */) *ServerConnectionPool {

ctx, cancel := context.WithCancel(context.Background())

return &ServerConnectionPool{

ctx: ctx,

cancel: cancel,

reconcileCh: make(chan struct{}, 1), // ✅ coalescing buffer

logger: logger,

// ... init other fields ...

}

}

// ✅ GOOD PATTERN: Non-blocking signal helper; bursts coalesce into a single pending signal.

func (bp *ServerConnectionPool) trySend(ch chan struct{}) {

select {

case ch <- struct{}{}:

default:

// already queued; coalesced

}

}

// triggerReconcile only *requests* reconciliation; never performs it inline.

// ✅ GOOD PATTERN: no work on the caller's goroutine, prevents stampedes.

func (bp *ServerConnectionPool) triggerReconcile() {

bp.trySend(bp.reconcileCh)

}

// ✅ GOOD PATTERN: Public starter that owns the worker lifecycle.

func (bp *ServerConnectionPool) Start() {

go bp.reconcileWorker()

}

// ✅ GOOD PATTERN: Graceful shutdown.

func (bp *ServerConnectionPool) Stop() {

bp.cancel()

}

// reconcileWorker serializes reconciliation and coalesces bursts.

// ✅ GOOD PATTERN:

// - Single-threaded worker → no concurrent ensureCapacity() runs

// - Periodic safety net with light jitter to avoid thundering herds

// - Drain queue before each run to collapse multiple signals into one

func (bp *ServerConnectionPool) reconcileWorker() {

jitter := func(base time.Duration) time.Duration {

// small ±10% jitter

n := time.Duration(float64(base) * (0.9 + 0.2*rand.Float64()))

return n

}

ticker := time.NewTicker(jitter(5 * time.Second))

defer ticker.Stop()

bp.logger.Debug("Reconciliation worker started", zap.String("pool", bp.GetName()))

defer bp.logger.Debug("Reconciliation worker stopped", zap.String("pool", bp.GetName()))

// Optional: run once immediately on startup

bp.ensureCapacity()

for {

select {

case <-bp.ctx.Done():

return

case <-ticker.C:

// ✅ Periodic reconciliation as a safety net

bp.ensureCapacity()

// reset ticker with jitter to spread load

ticker.Reset(jitter(5 * time.Second))

case <-bp.reconcileCh:

// ✅ Drain any queued signals: burst -> single reconciliation

for {

select {

case <-bp.reconcileCh:

// keep draining

default:

bp.ensureCapacity()

goto CONTINUE

}

}

}

CONTINUE:

}

}

// ensureCapacity is the single authoritative place that:

// 1) Cleans unhealthy queued conns

// 2) Computes current vs target

// 3) Grows or shrinks the pool

// 4) Emits metrics/logs

func (bp *ServerConnectionPool) ensureCapacity() {}

// ────────────────────────────

// Event sources that *request* reconciliation

// ────────────────────────────

// Health watcher: when a server flips health, request reconcile.

// ✅ GOOD PATTERN: do not call ensureCapacity() here; just signal.

func (bp *ServerConnectionPool) startHealthWatcher(healthCh <-chan HealthEvent) {

go func() {

for {

select {

case <-bp.ctx.Done():

return

case ev := <-healthCh:

if ev.Changed {

bp.logger.Debug("health change → reconcile",

zap.String("server", ev.ServerID))

bp.triggerReconcile()

}

}

}

}()

}

// Config watcher: when scale target changes, request reconcile.

// ✅ GOOD PATTERN: apply config change, then signal worker.

func (bp *ServerConnectionPool) startConfigWatcher(cfgCh <-chan ScaleTarget) {

go func() {

for {

select {

case <-bp.ctx.Done():

return

case target := <-cfgCh:

// update internal target state...

bp.logger.Debug("scale target changed → reconcile",

zap.Int("target", target.Connections))

bp.triggerReconcile()

}

}

}()

}

- Single-threaded worker serializes reconciliation

- Buffered channel coalesces bursts into single operations

- Periodic safety net with jitter prevents thundering herds

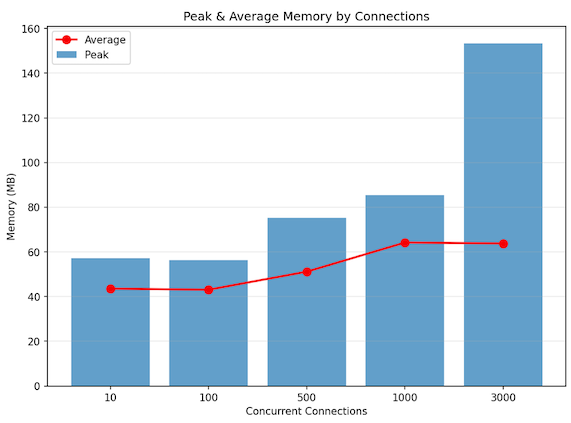

Local performance test setup and results

Test Setup

| Component | Configuration |

|---|

| Proxy | Go-based WebSocket proxy |

| Backends | 3 × Echo WebSocket servers |

| Load | 3,000 connections simultaneously (no ramp-up) |

| Traffic | 1 KB text messages @ 100 msg/s per connection |

Results

| Metric | Value |

|---|

| Concurrent sessions | ~3,000 stable |

| Throughput | ~300K messages/sec |

| Peak memory | ~150 MB |

| Average memory | ~60 MB |

| CPU usage | ~4–5% of 12 cores |

Performance comparison summary

Conclusion

After deploying the new Go-based proxy, we observed major improvements across performance, scalability, and stability:

| Category | Python (FastAPI + asyncio + Gunicorn) | Go (Goroutines + Channels + Atomics) | Improvement |

|---|

| CPU usage | ~12 cores × 40–50% | ~12 cores × 4–5% | ~90% reduction |

| Memory usage | ~25 GB | ~60–150 MB | ~99% reduction |

| Scalability | Limited to hundreds | Sustains thousands | 10x scale |

Key Takeaway: Design concurrency as independent, communicating processes — not as shared mutable state under protection.

References

- Go Concurrency Patterns - golang.org/doc/effective_go

- gorilla/websocket - github.com/gorilla/websocket

- Python asyncio Event Loop - docs.python.org